The Desktop Metaphor

How physical space shaped digital interfaces

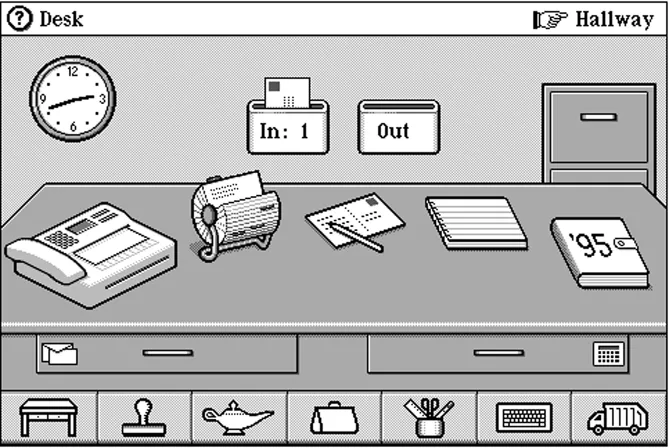

What do you see when you turn on your computer? That’s right, a desktop. The desktop is a spatial metaphor. One that is derived from the physical desks we used to work on, instead of our laptops. The ‘desktop’ used to be your main work area, now it’s our operating system.

Before the introduction of the desktop metaphor, interaction with computers was far from straightforward for the average person. It required typing commands in a command-line interface, which meant users needed to memorize specific commands and syntax. This approach limited computer usage to those willing to invest substantial time in learning these commands, effectively creating a barrier to entry.

The desktop metaphor revolutionized this by leveraging familiar concepts from the physical world to make computing accessible. Instead of having to remember abstract commands, users could interact with elements that resembled real-world objects - files, folders, and a workspace that mimicked a physical desktop. What once required specialized knowledge now became intuitive: drag a file, organize items in folders, discard things in a trash can. The desktop became a visual space where one could see and manipulate a 1:1 representation of a system. Instead of having to remember file locations or use commands to move files around, users could see their files represented as icons on their screen.

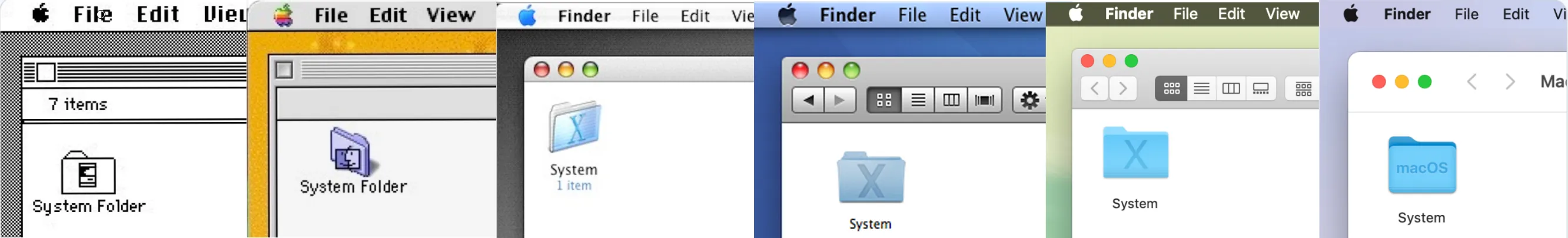

A screenshot of MacOS system design evolution over the years:

Spatial Organization

Software is incredibly complicated. To function well, we need to navigate complex applications, especially in professional tools and operating systems. We also have limited working memory. But the advantage of having a 1:1 visual representation is that we don’t need to know the exact location of a file path when we can simply locate the file with a visual representation and the help of the visual location. For instance, we can navigate to our Desktop, then open a specific folder, and finally locate a particular file within that folder. We don’t have to memorize the path; we can see the information. Visual information is much easier to digest than verbal descriptions.

In his writing on the topic, Andy Matuschak refers to the three ways working memory helps us out in software:

-

We can avoid memorizing commands when they’re visible in menus and toolbars.

-

We can avoid memorizing file paths when we can simply navigate to files through a spatial file explorer.

-

We can avoid memorizing document context when it’s directly represented on the canvas or in a panel on the screen.

The desktop metaphor leverages spatial interfaces, where objects are laid out in a space, creating a form of external cognition. This approach allows for easier organization and retrieval of information. Imagine a desk where you’ve arranged paper documents, books, and notes in a specific way. Even without actively thinking about it, you develop a sense of where things are (spatial memory) and how to interact with them.

By making items visible, it reduces the user’s need to remember exact locations (recall), instead allowing them to recognize items in their locations. This approach significantly reduces the mental load on users and makes interactions more intuitive.

The Downside of Metaphors

But there’s a downside to metaphor-based user interfaces. They only work if you’re familiar with the metaphor being used. The classic desktop metaphor works because most adults have used physical desks with files and folders. But what about people who have never worked with such systems, like children born into the digital age who might find the metaphor as foreign as using a command line?

Metaphors also tend to limit user interface design to what would exist in the physical world. A file might be stored in many folders in a computer, but in the desktop metaphor, we’re stuck with it being in one place. With the rise of virtual reality and other spatial computing technologies, we’re starting to see interfaces that break free from these constraints, leveraging depth, volume, and human perceptual abilities in ways that traditional desktop interfaces can’t.

Limited by Metaphors

The entire world is spatial. Our brains have evolved to operate in these physical environments, and from birth, we develop a mental map of the space around us. We’re also not only visual, but multi-sensory beings, learning to perceive the world through all our senses. However, our interfaces today don’t leverage anywhere near the full range of our perceptual capabilities.

We need to move beyond static metaphors and explore the rich potential of creating interfaces that tap into what makes us uniquely human. This is a vast, largely untapped design space where we can draw on what we understand about human perception, motor control, memory, and embodied cognition to create interfaces that feel as natural to use as physical space itself.

Beyond metaphors

We don’t have to use metaphors. I think we need to make a distinction between spatial interfaces and metaphors. Spatial interfaces leverage our innate understanding of physical space without necessarily relying on real-world metaphors. Take for example Twitter’s interface or file search, these don’t mirror physical-world concepts but still organize information in a way that leverages our spatial understanding.

But even beyond spatial interfaces, novel interfaces should also aim to leverage physical spaces and the way that our body and brains interact with the world. After all, it seems foolish to ignore millions of years of evolution.

For now, we will keep using the desktop metaphor. But the interesting thing is that as the interface evolves into something beyond the desktop, we’ll keep the name “desktop”. Just like “phone” is a poor description for our modern smartphones which do so much more than what a phone should do. I’m curious to see what lies ahead, the possibility of new operating systems with novel interfaces that leverage a broader range of our human perceptual abilities.

Reference

Concept of this essay was heavily influenced by “The Desktop Metaphor”